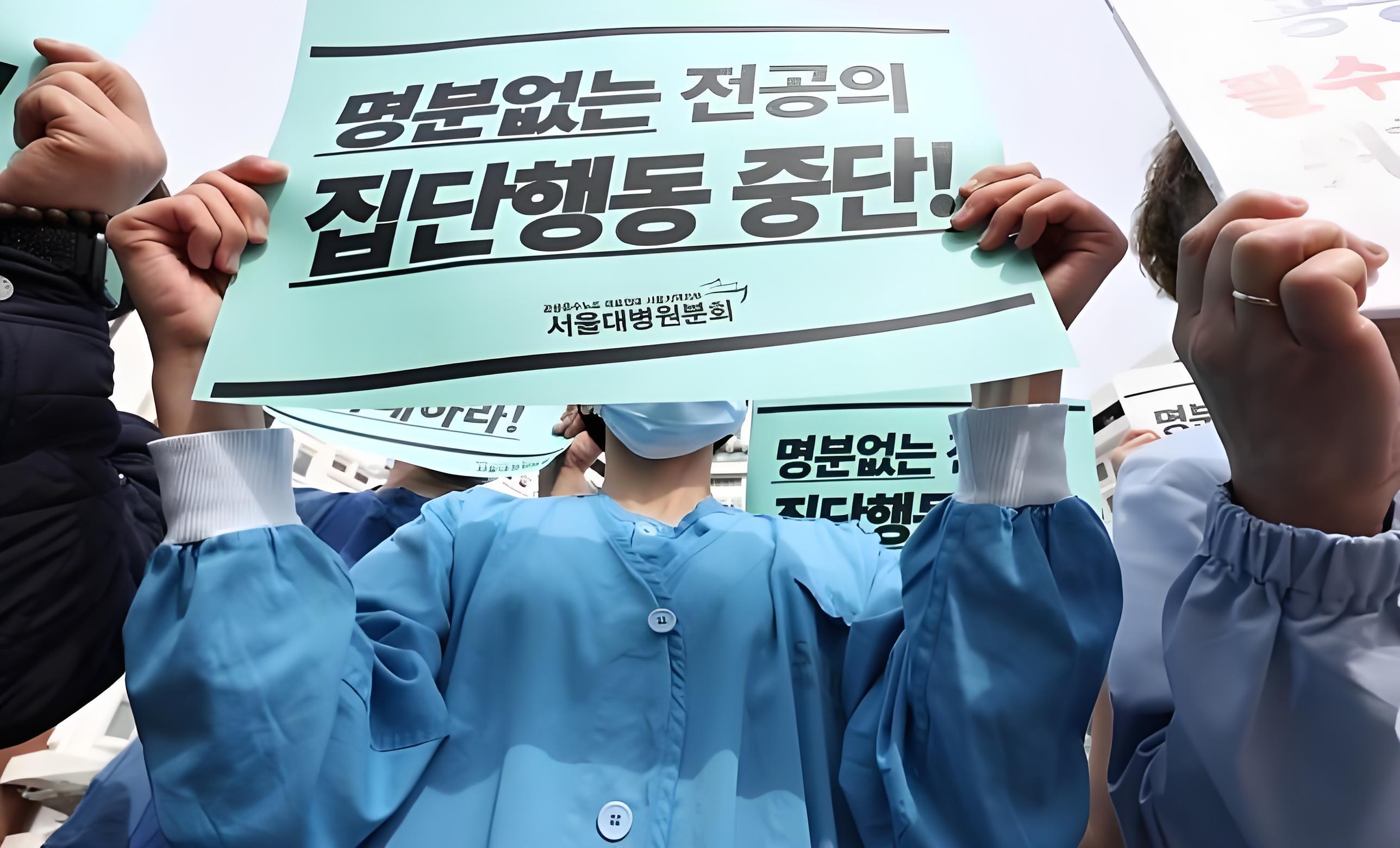

According to reports from South Korean media on August 31, the 18-month "resignation wave" crisis triggered by interns and resident doctors opposing the medical school enrollment expansion plan has finally come to an end. Most affected doctors will return to work on September 1, which is expected to ease the severe staffing shortage in South Korea's healthcare system.

Citing sources from the medical industry, multiple South Korean media outlets stated that major hospitals have completed the recruitment of interns and residents for the second half of this year. The Ministry of Health and Welfare will release the specific number of returning doctors and newly hired staff within a few days. As per media reports, most of the doctors who previously left their posts have agreed to return.

In February 2024, the South Korean government led by then-President Yoon Suk-yeol announced a medical school enrollment expansion plan. It decided to increase the annual enrollment quota of medical schools by approximately 2,000 students over five years starting from the 2025 academic year, aiming to address the shortage of doctors.

South Korea's medical community strongly opposed this expansion plan, arguing that it would lead to issues such as over-medicalization. Tens of thousands of interns and residents successively submitted their resignations and went on strike, disrupting the normal operation of medical institutions. In response, the South Korean government elevated the crisis level of the national healthcare system to the highest "severe" grade.

In April this year, the government softened its stance and announced that it would restore the enrollment quota to the pre-2025 level starting from the 2026 academic year. However, most of the doctors who had left their posts still refused to return. After Lee Jae-myung took office as president, he instructed relevant departments to explore feasible solutions through dialogue with the medical community. Last month, the South Korean government and representatives from the medical sector re-established a negotiation mechanism to discuss plans for doctors' return to work and other related matters.

According to South Korean media, with the large-scale return of interns and residents, the workload pressure on major hospitals will be alleviated, and medical services that were suspended due to staffing shortages will resume. The government plans to consider lowering the crisis level of the healthcare system once the situation stabilizes.

The impact of the doctor strike was far-reaching and severe. As the "resignation wave" spread, Jehong, a former professional Overwatch player and South Korean online streamer, was admitted to the emergency room of a hospital at 2 a.m. after a serious car accident. However, he was devastated to find no on-duty doctors available. Jehong then urgently contacted nearly 20 to 30 hospitals, only to receive the same response: "No doctors available." It was not until 8 hours later, at 10 a.m. on the 21st, that he finally underwent surgery. Medical staff warned that a further delay could have been life-threatening. This incident occurred just two days after the doctor strike began.

Twelve hours after Jehong's surgery, data from the Ministry of Health and Welfare showed that among 100 hospitals surveyed, 9,275 residents (accounting for 74.4% of the total resident workforce) had resigned, and 8,024 of them had already left their posts. The first wave of strikers mainly came from Seoul's "Big Five" general hospitals, including Seoul National University Hospital, Severance Hospital, Samsung Medical Center, Asan Medical Center, and Seoul St. Mary's Hospital. Later, major local hospitals such as Pusan National University Hospital and Chonnam National University Hospital also joined the strike, expanding the scope of the "resignation wave." Additionally, over 10,000 medical students suspended their studies in solidarity.

The anger of South Korean doctors was directed at the government's medical school enrollment expansion plan announced on February 6: starting from 2025, the annual enrollment of medical schools nationwide would increase by 2,000 students, raising the total quota from the current 3,058 to 5,058. This 65% increase would result in an additional 10,000 doctors in South Korea's hospitals over five years.

Kwon Soon-man, a professor of public health at Seoul National University, bluntly stated: "More doctors mean greater competition and potential reductions in doctors' future incomes." In South Korea, doctors belong to the upper echelons of the social elite. According to 2022 OECD data, South Korean doctors are among the highest-paid in the world. Specialists at major general hospitals in South Korea earn an annual salary of approximately $200,000, which is more than six times the national average income and ranks first among OECD member countries. Influenced by meritocracy, being a doctor has long been the top career choice for South Korean teenagers. However, becoming a doctor in South Korea is extremely challenging. Professor Kwon pointed out that the root problem lies in government regulations. South Korea has one of the strictest doctor qualification systems globally: in addition to 6 years of undergraduate study, aspiring doctors must complete 4 years of residency training and 3 years of specialist training. This system not only imposes heavy academic pressure on doctors but also leads to the waste of medical resources.

As many have worried, such a large-scale annual increase in medical student enrollment will exacerbate the already serious "medical school black hole" phenomenon, and experts fear it will lead to a decline in the quality of medical education. Zhu Xiu-hu (transliterated) expressed pessimism: "South Korea's medical sector is already on the verge of collapse. If the number of doctors increases further, it will worsen the medical crisis and drive up medical expenditure. Doctors will find it too difficult to work in such an environment, and many will abandon their careers... Unimaginable consequences will follow."

Statistics from the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service show that residents account for approximately 40% of the total doctor workforce in each of the "Big Five" hospitals. A survey conducted by the Korean Medical Association revealed that residents work an average of 80 hours per week—nearly 30 hours more than most other doctors—while their monthly average salary is far lower than that of regular specialists. This explains why residents are always the first to go on strike in every doctor protest in South Korea. The departure of these key frontline medical personnel exerts enormous pressure on the government but also causes an immediate consequence: the rapid collapse of medical order.

Regardless of whether there is an absolute shortage of doctors, the government and the medical community agree on one point: South Korea's healthcare system has serious structural flaws. On the evening of February 20, during the "100-Minute Debate" program on South Korea's MBC TV, the government and the medical community engaged in a fierce debate over their respective positions. Yoo Jeong-min, head of the Strategy Team at the Central Disaster and Safety Countermeasures Headquarters, mentioned that there is a severe shortage of doctors in some regions. In contrast, Jeong Jae-hoon (transliterated), a professor of preventive medicine at Gachon University, argued that the so-called "shortage" is mainly caused by uneven distribution rather than an overall lack of doctors. In other words, this is essentially a structural issue, and expanding medical school enrollment only treats the symptoms rather than addressing the root cause.

South Korean media pointed out that doctors oppose the government's expansion plan because they believe it will lead to an oversupply of medical resources, threatening their incomes and career development. This situation is analogous to a taxi driver who spent a huge sum to purchase a license plate, only to have the government suddenly lift the license plate restriction, allowing anyone to drive a taxi. As a result, the driver's income is immediately halved, and their investment becomes worthless. Doctors face a similar dilemma. The average annual salary of South Korean doctors is as high as

180,000,whichremainsasubstantialamountevenaftertaxes.However,thecostofbecomingadoctorisenormous:ahighschoolgraduateneeds13to19yearsofeducationandtrainingbeforetheycanstartearninganincomeasadoctor.Incomparison,theaverageannualsalaryinotherindustriesinSouthKoreaisonly 40,000, and most careers require only 4 to 6 years of education.

If the expansion plan had been successfully implemented, it would have been the first increase in South Korea's medical school enrollment since 1998. In fact, not only has the annual enrollment quota of medical schools remained unchanged for 27 years, but it was also reduced from 3,273 to 3,058 between 2000 and 2006, and has stayed at that level ever since. For years, the South Korean government has been seeking to expand medical school enrollment, regarding it as a key measure for healthcare reform, but has repeatedly failed. In 2000, the government agreed to reduce medical student enrollment after proposing a separation of medical and pharmaceutical services, which triggered a five-month-long large-scale doctor strike. To appease the medical community, the government ultimately agreed to cut medical student enrollment by 10%. South Korea's last major doctor strike occurred in 2020, when the Moon Jae-in government also proposed an enrollment increase of 400 medical students per year. This plan also faced fierce opposition from the medical community and was eventually halted due to the pressure of the COVID-19 pandemic.

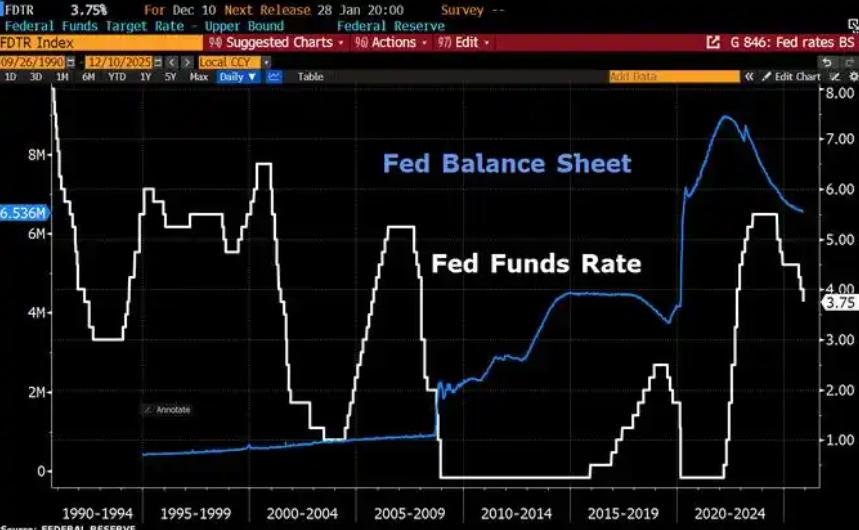

Since 2022, the Fed has cumulatively reduced its balance sheet by $2.4 trillion through quantitative tightening (QT) policies, leading to a near depletion of liquidity in the financial system.

Since 2022, the Fed has cumulatively reduced its balance sh…

On December 11 local time, the White House once again spoke…

Fiji recently launched its first green finance classificati…

Recently, the European Commission fined Musk's X platform (…

At the end of 2025, the situation in the Caribbean suddenly…

The U.S. AI industry in 2025 is witnessing a feverish feast…