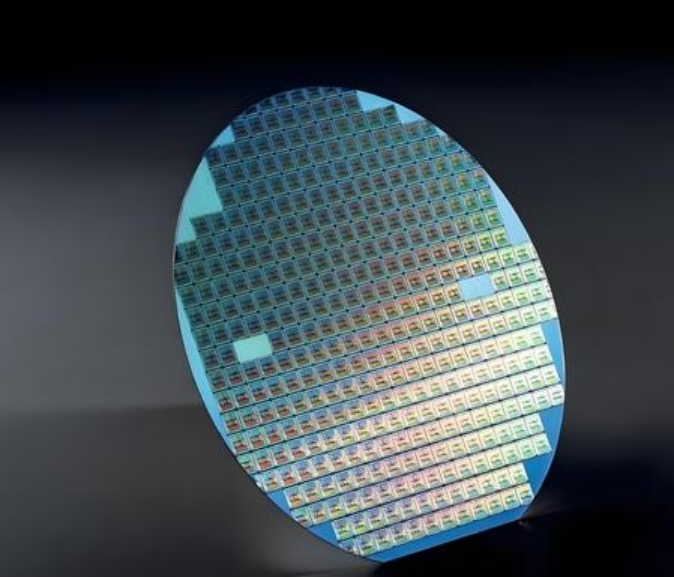

In October 2025, NVIDIA's first Blackwell chip wafer manufactured in the United States was officially unveiled. This chip, produced by TSMC's Arizona factory, is regarded by the US government as a milestone achievement in the three years since the implementation of the Chips and Science Act. However, the reality that chip wafers still need to be transported back to Taiwan, China for packaging reflects the complex predicament of the United States in promoting the localization of its semiconductor supply chain. This industrial support plan, which cost over 76 billion US dollars, is reshaping the global chip industry landscape and has also triggered a global game over subsidy efficiency, technological autonomy and trade balance.

The core objective of the US Chips and Science Act is clear: to increase the country's leading global chip production capacity to 20% by 2030 and reduce its reliance on the supply chain in East Asia. Since the bill was introduced, $39 billion in production subsidies and $11 billion in research and development funding have successfully attracted global giants to enter the field. TSMC is investing 65 billion US dollars in Arizona to build three wafer fabrication plants, with plans to mass-produce 2-4 nanometer advanced process chips. Samsung is advancing its logic chip production project in Texas. Intel, on the other hand, has stepped up its efforts in building local factories and research and development facilities. Data shows that capital expenditure in the US semiconductor sector has been continuously rising from 8.17 billion US dollars in 2022. The Boston Consulting Group predicts that the share of US wafer fabrication capacity will increase from 12% in 2020 to 13% by 2030. The job market is also reaping short-term benefits. The bill is expected to create 93,000 temporary construction jobs and 43,000 permanent jobs, becoming a significant highlight of the return of US manufacturing.

But behind the glamorous figures, the deep-seated shortcomings of domestic manufacturing are gradually being exposed. The most prominent problem is the high cost. The cost of building a wafer fabrication plant in the United States is much higher than that in East Asia. The average annual subsidy for each permanent job is as high as 185,000 US dollars, which is twice the industry average annual salary. More crucially, the United States has yet to break free from its reliance on core technologies: extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUV) equipment is completely dependent on Dutch ASML, and high-end packaging technologies are still concentrated in the hands of East Asian enterprises. This makes it difficult for "Made in the USA" chips to achieve full industrial chain autonomy. The concerns at the enterprise level are equally obvious. Many manufacturers complain that customers are reluctant to pay a premium for domestically produced chips and are more inclined to choose products with better cost performance from East Asia.

To break through the predicament of advancement, the US government is brewing more radical policy tools. According to The Wall Street Journal, the US plans to introduce a new "equal ratio" regulation for chip imports, requiring enterprises to have a 1:1 ratio of domestic production capacity to overseas imports. Those that fail to meet the standard will face a 100% tariff. This policy aims to force enterprises to shift their production focus to the United States, but the industry warns that its feasibility is questionable: the chip supply chain involves multiple links such as design, manufacturing, packaging, and testing, and the calculation of tariffs is extremely complex. At the same time, the domestic industrial support in the United States is not complete and cannot cover all the production demands of high-end chips. Currently, the US Department of Commerce is conducting an investigation into the impact of chip imports on national security, and a new round of tariff measures is on the verge of being introduced, which may further intensify global trade tensions.

The US-led restructuring of the chip industry has triggered a global subsidy race. The EU has introduced the "European Chips Act", Japan has intensified its support for enterprises such as Rapidus, South Korea has continued its tax incentives for Samsung and SK Hynix, and China has supported the development of domestic enterprises through industrial investment funds. The global semiconductor trade pattern has also been adjusted accordingly. In 2023, the semiconductor import and export volumes of the United States and China reached 630 million US dollars and 290 million US dollars respectively, which was basically on par with the trade with the European Union. However, in the field of mature process chips, the United States still relies on imports. This "fighting on its own" industrial policy has led to a risk of structural overcapacity in global chip production capacity, while the fragmentation of technical standards may increase industry costs.

The practice of the US chip localization movement shows that the global division of labor in the semiconductor industry cannot be reversed by short-term policies. Although the subsidy policy has driven huge investment, the three major bottlenecks of cost disadvantage, technological dependence and lack of supporting facilities make it difficult for the United States to achieve true industrial autonomy in the short term. For global technology enterprises, this game means that the layout of the supply chain needs to seek a balance among policy compliance, cost control and risk diversification. For governments of all countries, they need to be vigilant against the escalation of trade protectionism triggered by subsidy competitions.

From the wafer output at TSMC's Arizona factory to the new tariff regulations that have yet to be implemented, the path of localizing US chips is full of contradictions and challenges. This industrial restructuring is not only a contest between technology and capital, but also a profound adjustment of the global economic governance model. In the future, only by finding a balance between ensuring supply chain security and maintaining the efficiency of global division of labor can the sustainable development of the semiconductor industry be achieved. As the report of the Semiconductor Industry Association points out, the competition in the chip industry has long transcended the scope of a single country. Open collaboration and technological innovation are the fundamental ways to break through the current predicament.

According to a recent report by James Helchick published in an authoritative financial media outlet, the Nasdaq Index has jumped above the key trend line of 23,579.10 points, aiming for the historical high of 24,019.99 points.

According to a recent report by James Helchick published in…

On January 18th, local time, the so-called "Peace Committee…

Recently, Elon Musk has sought up to $134 billion in compen…

Amidst the global wave of technological transformation, art…

In January 2026, the remarks by US Treasury Secretary Besse…

Less than three weeks into 2026, transatlantic trade relati…